Are creative people likely to carry a genetic risk for mental diseases? A recent study published in Nature Neuroscience, indeed concluded that the genetically carried “risk scores for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder predict creativity”. This study is based on a widely carried collection of genetic samples of the population in Iceland. Living in Iceland, I experienced the discussion about that “data mining” and I also found a sample-donation kit in my mailbox.

My DNA donation kit, 2014.

I don’t want to address the fact that deCODE, the company collecting the DNA samples from about 100,000 Icelanders (which is a bit less than 1/3 of the population) used staff members from the national rescue team to go from door to door and ask people if they want to donate their DNA to a private company for unclear reasons. But in my opinion, there are several things wrong in that partial study derived from the donations:

First, this study addresses about 3% of the population, comparing them with ca. 30% of the countries’ total number. It seemlingly only takes into account Icelanders working in a profession considered by the authors to be “creative”. The icelandic population is quite remotely located, which is exactly why it is so attractive for massively genetic analyses as done by deCODE. Other populations might not be comparable with the icelandic one, since Iceland is a special case.

Second, the definition of creativity that is made by the authors is (and has to be) arbitrary:

Creative individuals were defined as those belonging to the national artistic societies of actors, dancers, musicians, visual artists and writers (n = 1,024 […]).

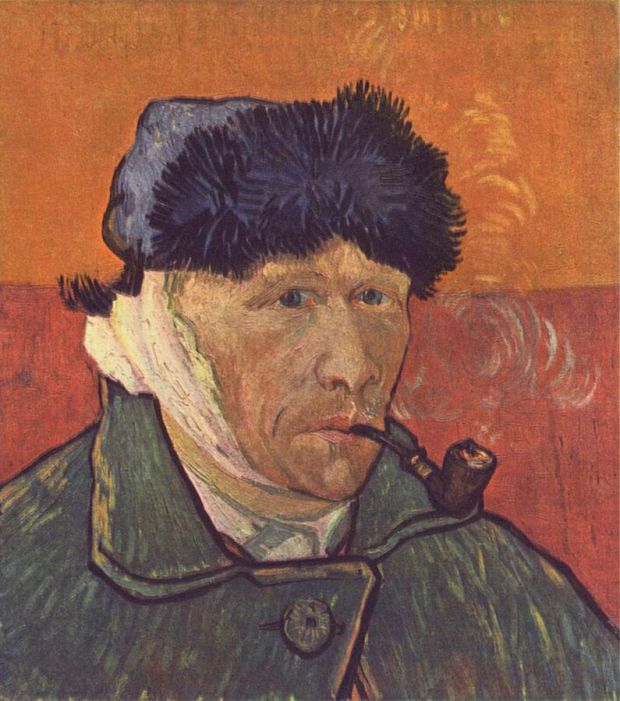

Are genius and madness genetically connected? Image: Vincent van Gogh

I fully agree to that in a study about creativity, that term needs to be defined. The choice of considering members of the artistic societies also seems to be also quite reasonable, but I see there one major issue: Not every creative person might work in a creative job. And vice versa, not every person working in a creative area might be actually creative. This point is also very nicely addressed in the hyperallergic blog, together with an interpretation of the observed correlation between the genetic risk and working in a creative environment:

If the distance between me, the least artistic person you are going to meet, and an actual artist is one mile, these variants appear to collectively explain 13 feet of the distance – David Cutler, geneticist at Emory University

Especially Iceland is famous for its vivid independent music scene and Icelanders are famous for writing and making music – besides working in all kinds of professions. About 10% of all Icelanders are likely to publish a book in their lives, but the study considers only 194 writers. On the other hand, creativity might not be the only prerequisite to work in a creative profession. Artists, actors, musicians and dancers also need a high degree of discipline, passion and self-confidence to persist in those fields.

That being said, I think that this study is a perfect case for positivistic interpretation of a result, suggesting that creativeness is linked to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. This result can only be valid for people who 1) are Icelanders, 2) participated in the DNA collection and 3) are member of a national artistic society. For all other creative people that primarily work as bus drivers, teachers, farmers, etc., this study does not draw any conclusion. My opinion.